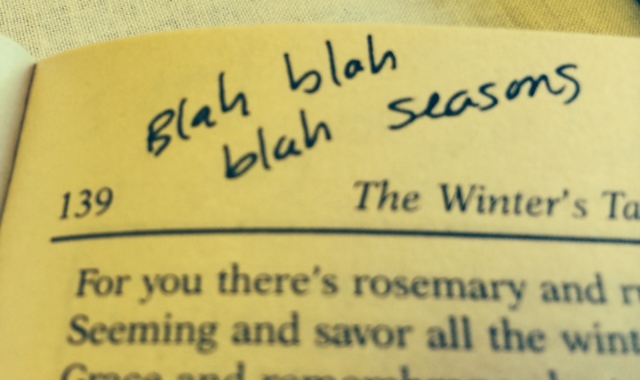

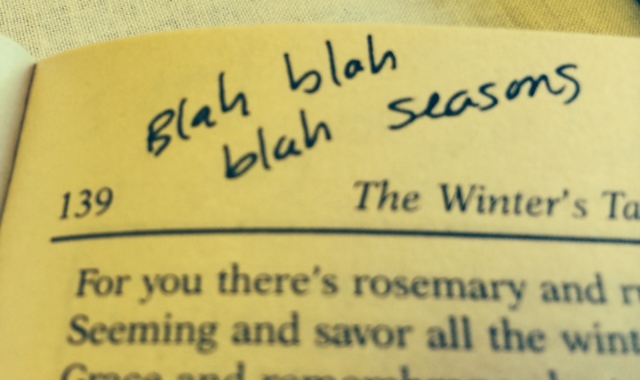

I feel a little silly for wondering why Shakespeare titled this play The Winter’s Tale, especially since I used to devote a week or so in 10th-grade English to the way seasons are used metaphorically in poetry, including Shakespeare’s – “Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day,” and so forth. But I suppose I can be forgiven, because back in Act II I didn’t fully understand that this is a play about time. Sixteen years pass between Acts III and IV, and Act IV, scene 1 consists entirely of a single speech by Time (that’s Time the dude, not time the abstract concept). The transition between Acts III and IV is jarring and feels totally alien to my experience of Shakespeare’s world – more on this newness in a moment. In Act II, I was wondering what winter had to do with anything in this play; by Act IV, I was writing things like this in the margin:

To a modern reader, a 16-year leap forward in the plot of a play or other narrative is almost de rigeur. Just about every sitcom I watched as a kid produced at least one flash-forward episode, in which the teen heartthrob character walked around with white dye in his hair and a pillow shoved down his pants, calling everyone else “sonny.” Most of the high modernists of the early 20th century found time troublesome in some way; a 16-year leap forward is nothing compared to the temporal antics of Faulkner, Joyce, Woolf, and Fitzgerald, and these writers were canonical before I was born.

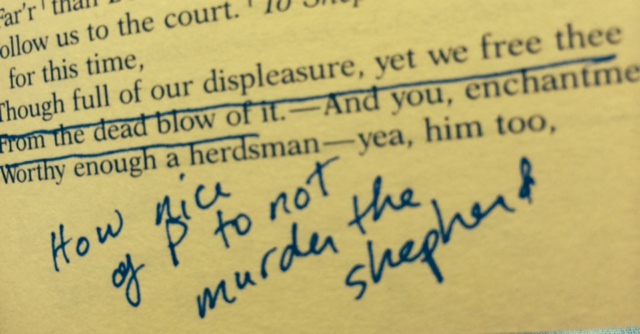

Act III, which is relatively brief, focuses on the consequences of the psychotic break Leontes experiences in Act II. Hermione is tried in court for the affair with Polixenes that Leontes swears she had, and Leontes decries as fraudulent the report from the Delphic oracle that he himself commissioned. Hermione delivers several long speeches in her own defense, and Paulina delivers a Julia Sugarbaker-style rant about how every time men think they’re omnipotent, they’re wrong. And Western literature can never have too many of those.

As far as I know, the idea of jumping ahead sixteen years in a staged drama was uncommon in the seventeenth century, if not entirely unprecedented. This move violates Aristotle’s “unities,” for one thing, and plays in this era tended to be oriented around solving a specific problem. While I know – and suspect that Shakespeare did as well – that it is entirely possible to let a problem sit around and fester for sixteen years or more – this kind of procrastination isn’t exactly best practice.

When the action resumes in Act IV, a character named “Time” – who is also called “the Chorus,” suggesting that he is somehow an individual and a group at the same time – appears and rattles off some rhymed couplets. “Now take upon me, in the name of Time, / To use my wings. Impute it not a crime / To me or my swift passage that I slide / o’er sixteen years, and leave the growth untried / Of that wide gap” (IV.i.3-7), he says, indicating also that he has the power to “o’erthrow law” (IV.i.8) and “o’erwhelm custom” (IV.i.9). Unlike Joyce and T.S. Eliot and Hemingway, who burst onto the literary scene with their bold new approaches to writing fiction and poetry in the early 20th century, this speech by “Time” gives the impression that Shakespeare is shuffling around a bit, saying, “So um yeah, there’s this new thing I want to try. You’ll probably hate it, but…” But he does know that he is doing something new here, and there is wisdom in this moment too, when Time reminds us that ancient things were once fresh and new and that the things that are new now will someday be “stale” (IV.i.13). In some ways, Time is introducing himself as an antagonist in this play – someone who will steal sixteen years away from what could have been the happier lives of many characters, especially Leontes and Perdita.

After giving birth to her baby in prison, Hermione dies of “swooning” during her trial, and Leontes orders that the baby – whom he wrongly insists is not his own – be put to death. Instead of killing the baby, though, Leontes’ courtier Antigonus gives the baby to a shepherd, who passes her off to another shepherd, and somehow or other the baby – named Perdita, meaning “lost” – ends up living with ashepherd family in Bohemia, not too far from where Polixenes is king. These were some jet-setting mythical ancient shepherds.

I couldn’t get past the idea that this play seems like – among other things – a retelling of Oedipus Rex. Common elements include the two sets of kings and queens, the abandoned baby bring processed through an underground railroad of stealthy shepherds, and the decision in both plays to consult the Delphic oracle. Technically the gap of time is present in Oedipus as well, but because Sophocles begins his play after Oedipus has committed his little oopsie with his father and mother and then has the past filled in via the monologues of older characters sharing what they remember, this gap is less conspicuous in Sophocles than it is in Shakespeare. Shakespeare tends to tell his stories in chronological order, though, so if he was using Oedipus as a source (and I don’t know for sure that he was) and he reordered the events to put them in order, the gap of time would have become a narrative necessity rather than something he invented.

There are differences between these two plays as well. The central theme in Oedipus is fate and free will. Everything bad that happens to Oedipus and his family happens because they chose to ignore the warnings of the Delphic oracle and tried to circumvent fate. Baby Oedipus was given to a shepherd not because his father was afflicted by sudden-onset paranoid schizophrenia like Leontes but because his parents had been given the terrible prophecy that their son would grow up to kill his father and marry his mother. Perdita, on the other hand, was given to the shepherds because her father couldn’t stand having her around and wanted her dead. Their reunion in Act V is not an act of unavoidable fate but the end of a great deal of scheming on the part of Polixenes, his son Florizell, Perdita, and Camillo, the servant who helped Polixenes flee from Sicily to Bohemia and then stuck around for sixteen years, like you do. The ending of the play is driven by coincidence, but not by fate. These characters create their own resolution – a comic one.

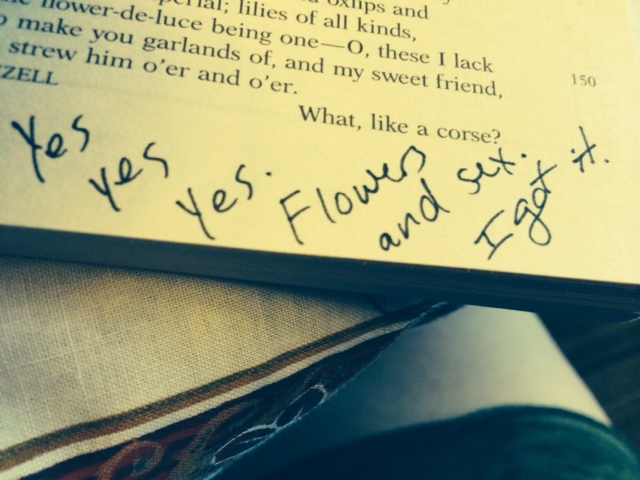

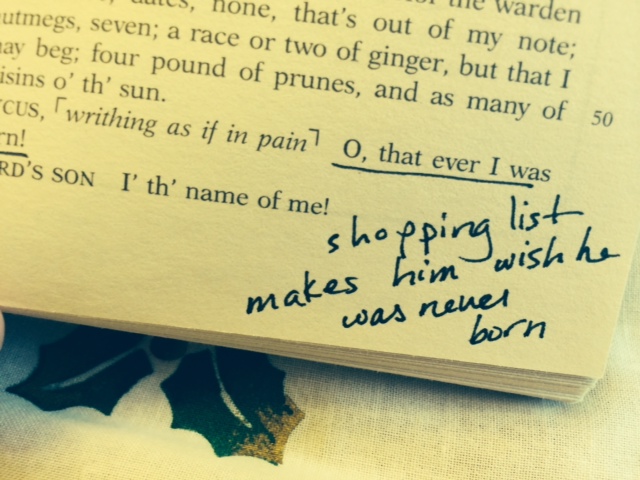

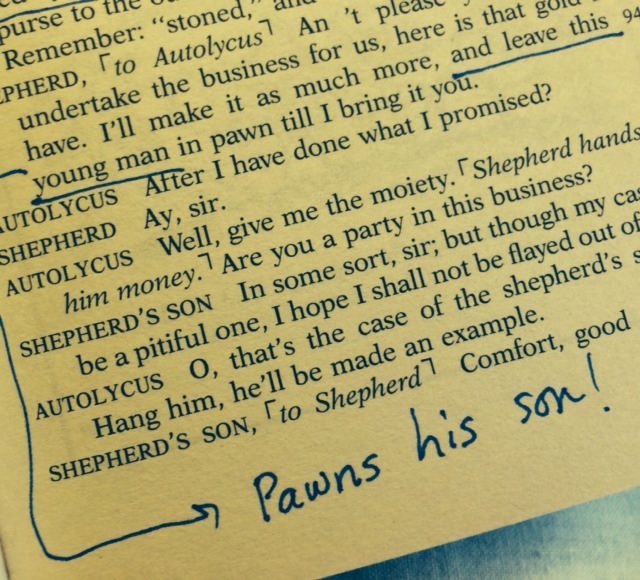

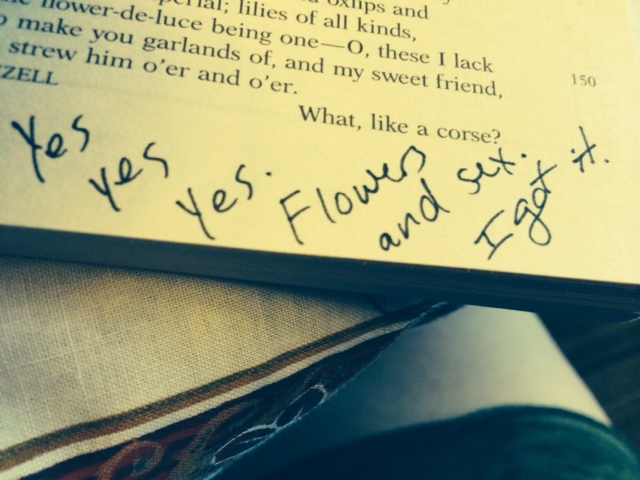

After Time announces in his soliloquy that shit is about to get weird, Shakespeare manages to slow time down to an absolute crawl by giving us an Act IV, scene iv that is almost 1000 lines long. The whole thing takes place at a “sheepshearing feast” and is about as exciting as this setting suggests. This is the scene in which Florizell (Polixenes’ son and heir) and Perdita fall in love, and a mini Romeo-and-Juliet subplot ensues. The sheepshearing feast reminds me of the fairy scenes in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in the sense that the usual distinctions among characters disappear. Everyone is dressed for “rustic” endeavors, and there almost seems to be something magical in the air that brings Florizell and Perdita together. However, this magic does not affect Polixenes, who lurks around and complains that his kid is about to bang the shepherd’s daughter, acting like Carson on Downton Abbey acts when any character whatsoever does pretty much anything. For us egalitarian types, there’s a delightful parallel scene when Perdita tells her (adopted) father, the shepherd, that she and Florizell are in love and that the prince wants to ask for her hand in marriage. The shepherd makes no acknowledgement whatsoever of their difference in status but focuses instead on whether Perdita really loves Florizell and whether Florizell will take care of her in the manner to which she has become accustomed. As rank and wealth and other social distinctions become irrelevant in this scene, the primary tension is between the young and the old – which again is a reference to time.

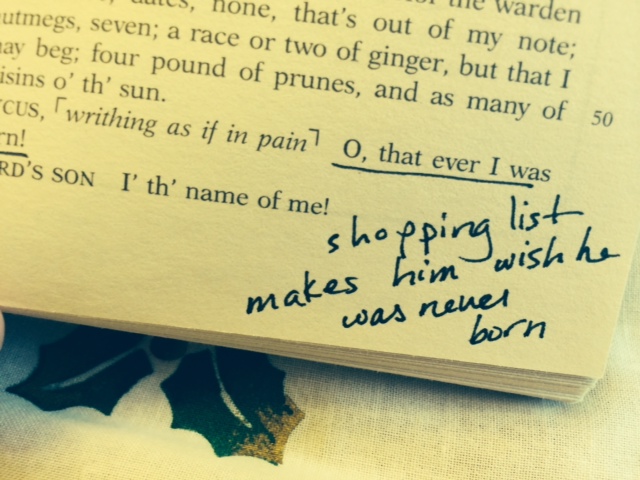

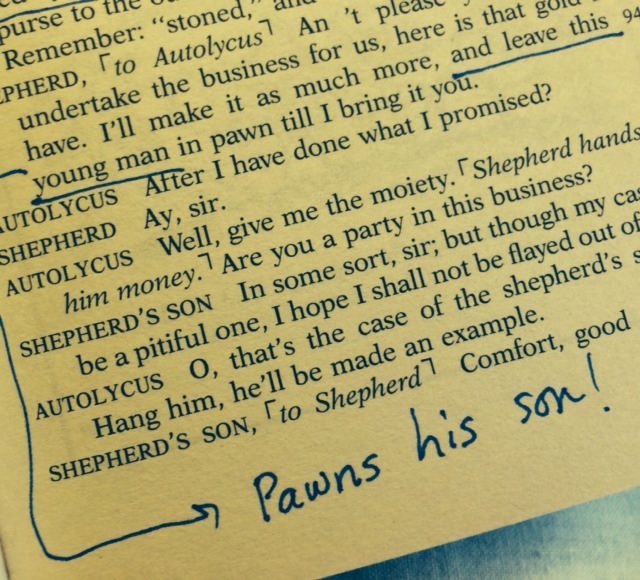

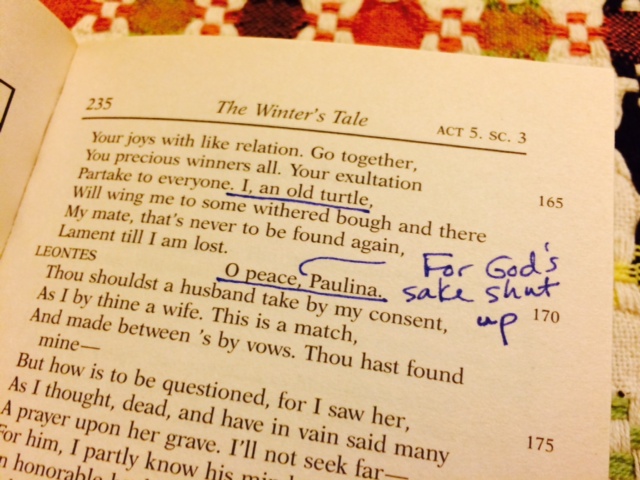

And it goes on and on and on, and I got a little punchy, entertaining myself with such marginal notes as these:

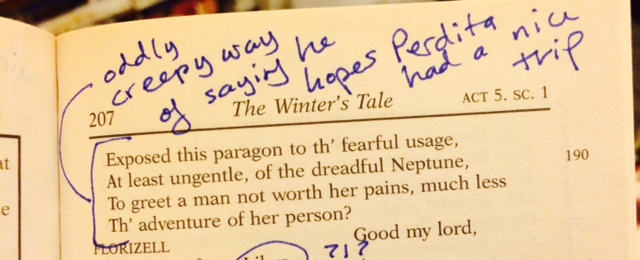

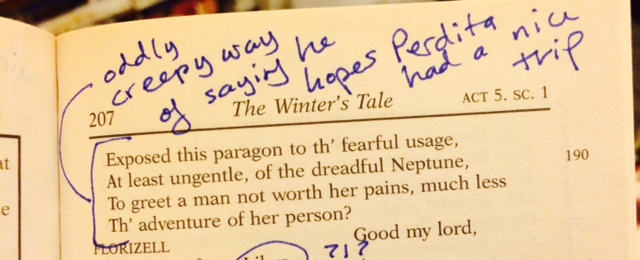

Act V brings us back to Sicily, where Paulina seems not to have experienced the gap of time at all; she’s still ranting to the king about what an asshole scumbag he is. The fact that she tortures Leontes with constant rhapsodies of how beautiful Hermione was comes in handy when Perdita turns up. Since Hermione’s appearance is painfully fresh on everyone’s mind in spite of the gap of time, they all recognize her immediately as Hermione’s daughter – since, you know, it was a weekend and all the DNA labs were closed. Much like George W. Bush on the subject of the WMD’s in Iraq, Leontes glosses over the fact that he went stark raving mad a while ago and acts as if he knew all along that Perdita was his daughter as well as Hermione’s, in spite of the fact that when they first arrive Florizell introduces Perdita as the prince of Libya and Leontes awkwardly tells her that he hopes Poseidon didn’t rough her up too much on the journey:

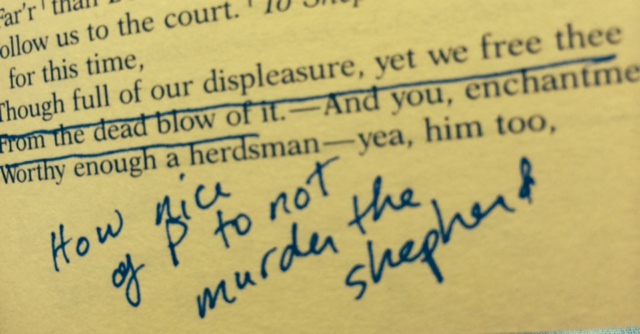

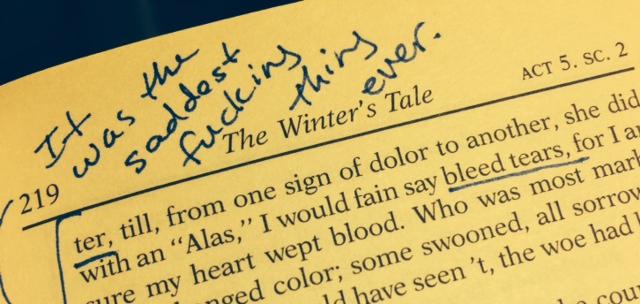

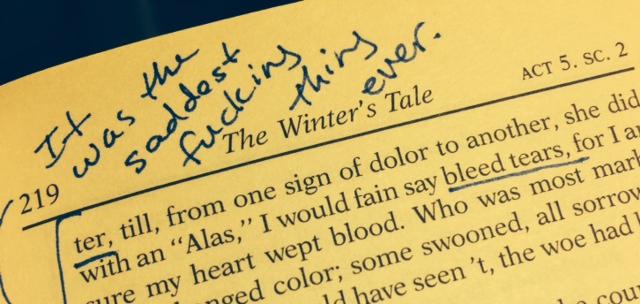

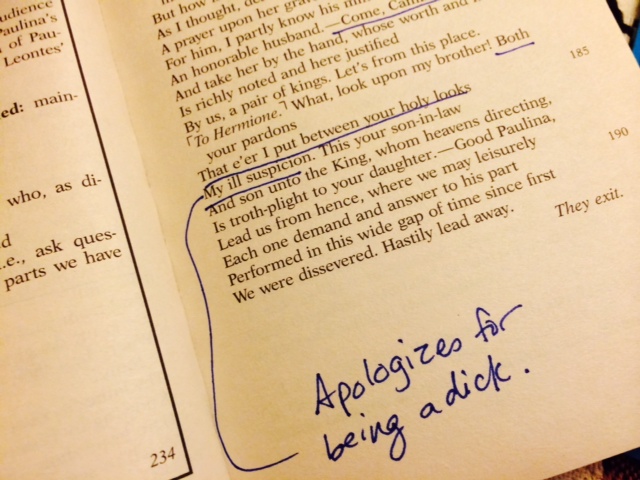

And then everyone sobs for about a thousand pages about how sad it is that Leontes was such an unspeakable asshole that it took sixteen years for everyone to reunite with one another, and I wrote this in the margin:

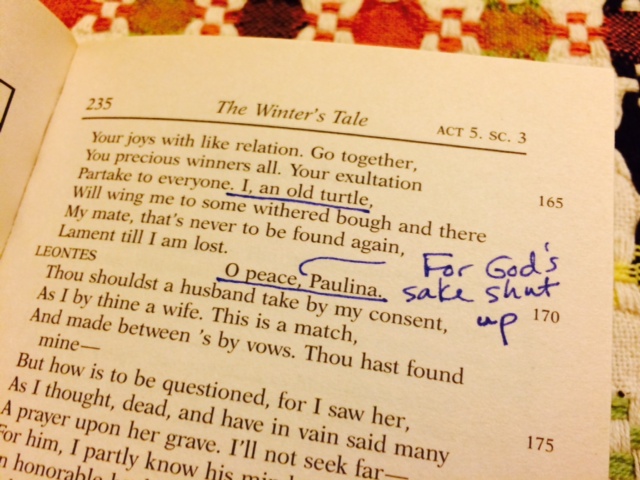

And then it turns out that Hermione isn’t really dead but just turned to stone. Leontes sneaks in a poignant line – “I am ashamed. Does not the stone rebuke me for being more stone than it?” (V.iii.43-44), and then we find out that Paulina knew all along that the “statue” of Hermione would eventually turn back into Hermione herself, making the fact that Paulina spent sixteen years torturing Leontes about his terrible judgment all the more sadistic. By the end I even sympathized with the guy, cheering him when he finally manages a mild rebuke of Paulina:

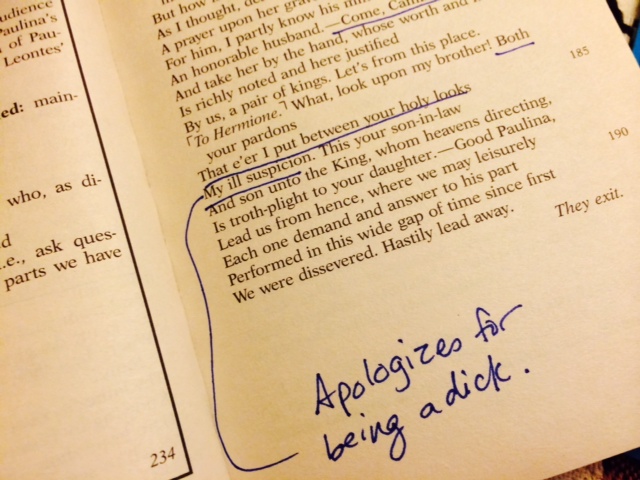

And then Leontes mans up and apologizes to Hermione –

– who has not aged in the sixteen years when she was turned to stone, meaning that not only does Leontes get his daughter back and the satisfaction of finally telling Paulina to shove it, he also gets to be a middle-aged man with a hot young wife. In other words, after straying from its traditional plot structure a bit, the play upholds society’s values, as comedies should. If this play took place today, instead of turning to stone Hermione could have just spent the last sixteen years in a luxury Botox clinic in the Berkshires.

This play made me snort a little, and Act IV, scene iv was pretty rough, but I’m glad I read it because of the levels of texture it added to my understanding of Shakespeare’s work as a whole. I think my favorite thing about Shakespeare – besides the dirty jokes – is the way all his plays talk back and forth to one another. The more of his work I read, the more I recognize them as all part of one story – a story that is about legitimacy, love, and the difficult but satisfying and supremely important work of blowing holes in bullshit.

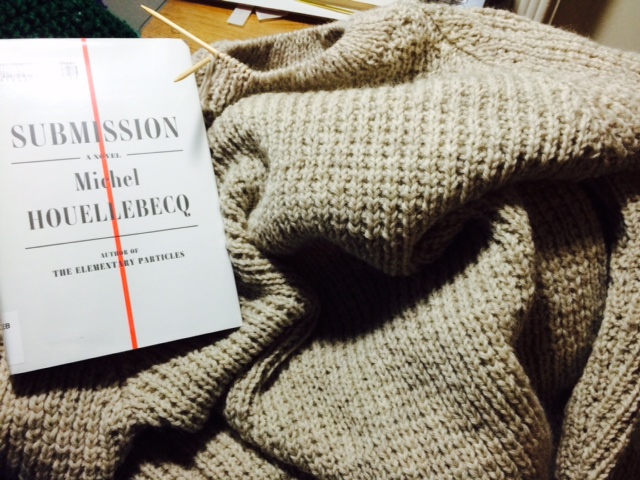

Here’s the deal. I have about fifty pages to go in Augustus, and I really, really want to finish it before I write a post about it, but I need to talk about something tonight. I’ve been whining in my head a lot for the past thirty-six hours about my cold and my cough and the fact that I’m in Florida and why is it colder here than it is at home and why did I not bring my puffy North Face jacket? I’m beginning to tire of the subjects since I’ve pretty much only had myself for company since my mom left on Monday morning, and these are the topics that my mind has been spinning around and around since she left.

Here’s the deal. I have about fifty pages to go in Augustus, and I really, really want to finish it before I write a post about it, but I need to talk about something tonight. I’ve been whining in my head a lot for the past thirty-six hours about my cold and my cough and the fact that I’m in Florida and why is it colder here than it is at home and why did I not bring my puffy North Face jacket? I’m beginning to tire of the subjects since I’ve pretty much only had myself for company since my mom left on Monday morning, and these are the topics that my mind has been spinning around and around since she left.