Paradise Lost is hard. It’s hard and intimidating and impossible to read without hearing Milton’s throaty voice laughing at you from wherever he is now – probably Purgatory. It’s also fascinating. This poem reminds me how much I love blank verse. It also reminds me that, regardless of what one thinks of Christianity as a religion or of Christianity’s role in history, there is no question that Christianity contains some of the best metaphors ever created by humankind. If there were Academy Awards for metaphors, Christianity would be Katherine Hepburn. If there were a Tour de France for metaphors, Christianity would be Lance Armstrong – and no, I’m not going to say “without the steroids.” Anyone who has studied any history at all knows that the Church spent the entire Middle Ages taking steroids.

The best way I know to deal with a difficult book is to imagine myself preparing to teach it. A teacher can’t show fear. When I was teaching, I tried to be always aware that for some kids, an English classroom where they are expected to read literature whose vocabulary and idioms are different from their own and where subjectivity and creativity are the determinants of success is the most terrifying place on earth. Everything I felt as a kid about a volleyball or basketball court, some kids feel about English class.

I have almost no formal training as a teacher. I took one education course as an undergrad, but this course focused on theory, not on practice, and I took a course as a grad student about how to teach basic composition. Everything else I know about teaching comes from trial and error and on borrowing or adapting ideas from colleagues. Somewhere along the line, though, I learned that the best way to deal with the fear of subjectivity and the fear or archaic language is as follows: 1) Simplify. Provide a series of steps that students can follow to filter away some of the distractions, 2) Relate the text to the students’ own life experiences, and 3) Build the complexity back up again by returning to the text and using the students’ increased understanding of the ideas in the text to help them build their confidence and skills in understanding the text.

If I were teaching Book 1 of Paradise Lost (which I would probably never do, unless I was teaching at the college level), here’s how I would begin:

First, I would review basic grammar, and then I would ask the students to underline the subject and verb of each clause. I know some teachers who would think this is an example of tedious busywork, and to that criticism I would ask the teacher to read the first sentence of Paradise Lost and tell me what it says without paying attention to the grammar. Here it is, in all its sixteen-line glory:

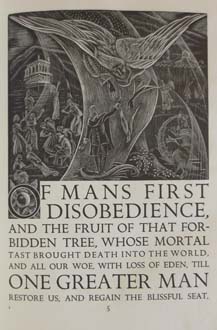

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, til one greater man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed,

In the beginning how the heavens and the earth

Rose out of Chaos: or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God, I thence

Invoke thy aid to my advent’rous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme. (I.1-16)

Got that? Yeah, I didn’t think so. Here’s what happens when you start to play with the grammar. First you look for all subject-verb pairs, which I’ve marked in boldface below:

Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world, and all our woe,

With loss of Eden, til one greater man

Restore us, and regain the blissful seat,

Sing, Heav’nly Muse, that on the secret top

Of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire

That shepherd, who first taught the chosen seed,

In the beginning how the heavens and the earth

Rose out of Chaos: or if Sion hill

Delight thee more, and Siloa’s brook that flowed

Fast by the oracle of God, I thence

Invoke thy aid to my advent’rous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above th’Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme. (I.1-16)

The grand total is eleven subject and verb pairs, including one subject (“man,” line 4) that has a set of compound verbs (“restore” and “regain,” line 5) and one verb (“rose,” line 10) that has a set of compound subjects (“the heavens and the earth,” line 9). Eleven subject-verb pairs means that the sentence has eleven clauses, so next we have to figure out which clauses are independent and which are dependent:

1. “whose mortal taste brought death into the world” (2-3) is dependent because it begins with a relative pronoun.

2. “til one greater man restore us, and regain…” (4-5) is dependent because it begins with a subordinating conjunction (“til” – short for “until”)

3. “Sing, Heav’nly Muse” (6) is independent. Students often miss this one because they forget that imperative verbs have an understood “you” before them. In this case, the understood “you” is the “Heav’nly Muse” being addressed, but not all imperative verbs will have a specific addressee given.

4. “that on the secret top of Oreb, or of Sinai, didst inspire” (6-7) is dependent because it begins with a relative pronoun. I would also point out that the subject of “didst inspire” is not “Muse,” even though the Muse is the one that did the inspiring. The subject of “didst inspire” is “that” – a relative pronoun that stands in for “Muse.” This can be hard for students to see as well.

5. “who first taught the chosen seed”(8) is dependent because it too begins with a relative pronoun.

6. “ how the heavens and the earth rose out of chaos” (9-10) is dependent. This is a noun clause that is serving as the direct object of “taught” (line 8). Noun clauses are always dependent.

7. “if Sion hill delight thee more” (10-11) is dependent because it begins with a subordinating conjunction (“if”).

8. “that flowed fast by the oracle of God” (11-12) is dependent because it begins with a relative pronoun (“that”).

9. “I thence invoke” (12-13) is independent. The “or” in line 10 is easy to miss, but it’s a coordination conjunction, and it is holding together this sentences two main clauses.

10. “That which no middle flight intends to soar” (14) is dependent because, once again, it begins with a relative pronoun. (Milton likes relative clauses, doesn’t he? What does this mean? Maybe nothing, but it’s worth paying attention to.)

11. “while it pursues” (15) is dependent because it begins with a subordinating adverb (“while”).

Now – I know that I may have lost a few readers over the course of this grammatical orgy. What?? you ask. This is supposed to make Milton’s language simpler and more accessible? If there’s one thing kids hate, it’s grammar! What’s the deal?

Yes, yes – thank you for your feedback. I’ll respond: First, while Paradise Lost is not easy, finding subjects and verbs is easy. Assigning students a manageable task while they are reading a difficult text gives them an anchor. Most students would probably miss a few of the subject-verb pairs that I listed above, but overall this is an entirely reasonable task for kids. It makes it easier for them to keep reading even when the text gets frustrating. I use this method myself – if there’s a line in Paradise Lost or in any text that I’m trying to figure out, I tell myself to find the subject and verb. If a sentence is well written, the subjects and verbs – especially the subjects and verbs of the main clauses – will operate almost like a short summary of the sentence. When we look at the subjects and verbs of the two main clauses in the sentence above, we find “Sing…Muse” and “I thence invoke.” Even though this sentence is totally overwhelming, a quick grammatical analysis reveals that all Milton is doing here, really, when the extra verbiage is trimmed away, is calling upon the Muse (we later learn that Milton’s muse is the Holy Spirit) for guidance and inspiration as he embarks upon this epic. Students who have read The Iliad and The Odyssey or other epics are familiar with the concept of invoking a muse at the outset of a poem. And that’s it – that’s all Milton is really doing here, in spite of the fact that all his literary feathers are puffed up like a male peacock in heat.

The second step in the procedure outlined above is to relate the text to the students’ own life experiences. There is little in this first sentence that will necessarily feel familiar to the students, but I would use this time to draw attention to the themes, motifs, and allusions present in this opening sentence. Any time I talk about Adam and Eve with students (and those two do seem to pop up all over the place in literature), I go back over the temptation of Eve by the serpent and the idea that eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil could supposedly make a person on par with God, and I ask students what they would have done. “Would you have eaten the apple? If you had a chance to know everything God knows, but you knew you would have to disobey a rule in order to do so, would you take that risk?” Almost universally, freshmen and sophomores say no, and juniors and seniors say yes. That, by the way, is as good a reason I can provide for the fantastic allure of teaching high school. That’s what it means to become an adult – to recognize one’s own complicity in original sin and to embrace and welcome the potential in all human beings to drive ourselves to ruin.

So much of Paradise Lost is about the tension between disobedience and freedom – which, of course, are the same thing. An authority figure (a parent, a teacher, a boss, the mercurial God of the Old Testament) furious because one of his/her subordinates has decided to tread his own path uses the word “disobedience,” but the rebellious child or employee who is burning rubber out of the parking lot of the hated home or school or job knows that this disobedience is the only route to freedom – and therefore must be honored as an essential component of that freedom.

And here’s what I would do next: I would lean in and make sure I had the eyes and attention of everyone in the room, and I would say, “That’s what Paradise Lost is: a gigantic middle finger held up to God. It’s about the fact that every time a real person or fictional character says “Yes, sir” and proceeds to follow an order to the letter, a story that could have been great curls up and dies. It’s about asserting oneself even when doing so is dangerous and stupid. It’s about the fact that the God of the burning bush does not have a monopoly on the right to say, ‘I am who I am. Now take off your damn shoes.’”

And then they would be hooked – in spite of the fact that the book is so damn hard. More soon.

I want you to teach Paradise Lost to me! This was awesome.

Thanks! I didn’t really say much about Book 1 beyond the first 16 lines, though. I may write a second post on Book 1 tomorrow or Thursday, just to cover some of the themes and Satan as a character and that sort of thing.

This is brilliant!! I loved it, especially the grammar. No, especially how you would teach it, and why you love teaching high school! Just amazing!

Thank you! Funny how this essay started out saying that I WOULDN’T teach it and ended up being about how I WOULD.

beautifully written. reading your experience felt like getting a glimpse at what i have always felt, teaching to Undergrad students in an Indian University where english is their second language. so you can imagine the magnified status of my problem as I try to cram their linguistically challenged 18 year old brains with the high volt dose of Paradise lost book 1. This grammar trick works like a charm, specially when they finally locate the principal verb “sing”. the primary problem in teaching Milton’s epic had always been “battling the hyperbaton(s)”

but it feels so satisfying when at least some of them finally show that light in their eyes, which is illuminated only by understanding something so beautiful and yet so distant from their field of experience.

will look forward to your future posts. thanks and regards.

Thanks so much! I can’t even imagine the struggle an ELL student faces when s/he reads Milton, although at least they have experience struggling with English, while a native speaker expects reading English to be easy. Thanks for reading our blog!